The Second World War was a global war, with the

Axis powers of Germany, Italy and Japan taking the opportunity to extend their territory.

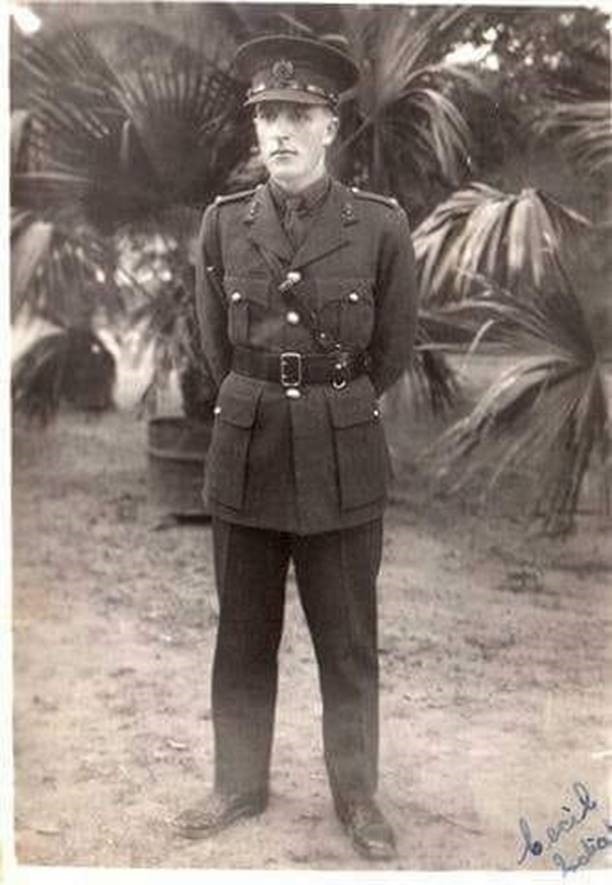

Many young men – like Cecil Kilpatrick – found themselves fighting in far-flung countries across Africa and Asia.

A month after war was declared, and while still a schoolboy at Campbell College in Belfast, Cecil signed up for the army. He was called up at 19, and, after some months in training, he volunteered to go to India.

In August 1940 Cecil sailed from Liverpool for Mumbai (then Bombay) via Sierra Leone and South Africa – all then part of the British Empire. Britain did not ‘stand alone’. The countries of the Empire contributed significantly with both people and resources.

Two and a half million men from India served in the war.

The flag of the company Cecil commanded

After just a few days of instruction in Urdu, Cecil was put in command of 200 Indian soldiers. Within weeks they were sent to oil-rich Iraq, where he found ‘It was 120 degrees in the shade and there was no shade’. They spent two years there protecting supply lines and building defences.

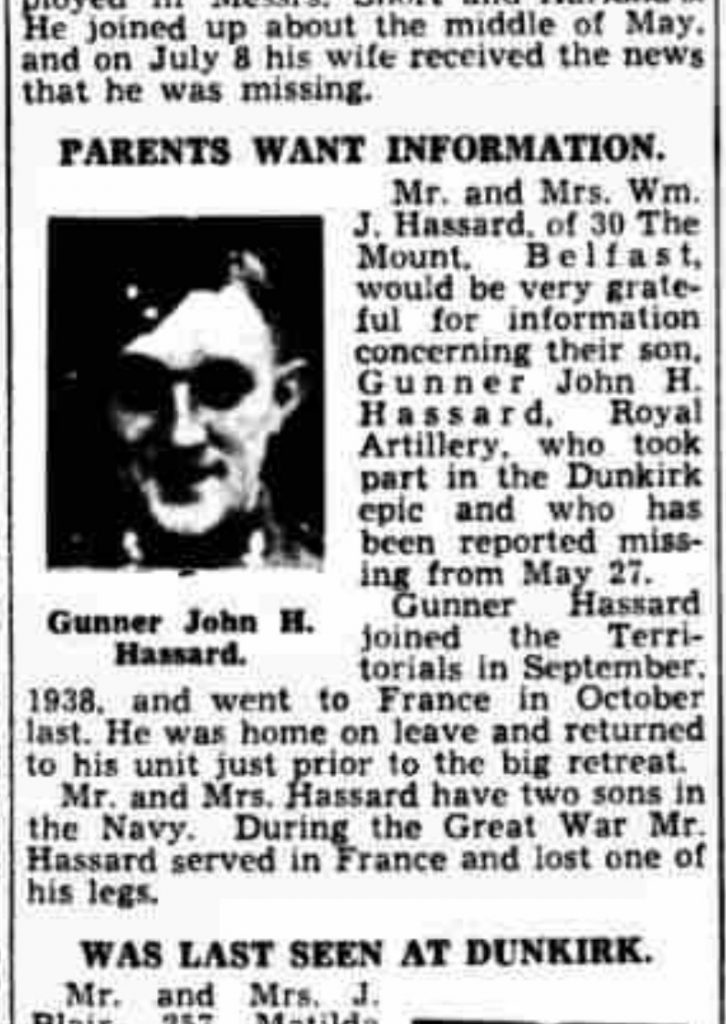

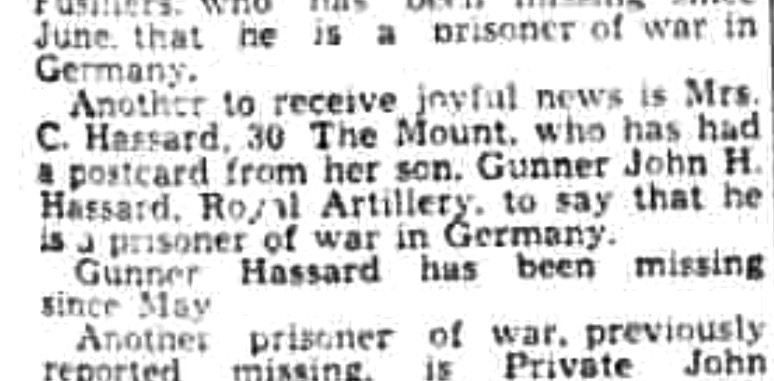

Another young volunteer from Northern Ireland, Bert Hassard, also found himself far from the front and far from home.

Having joined the Royal Artillery, he was reported missing in action.

His parents were desperate for news, and finally discovered that he was in a prisoner of war camp.

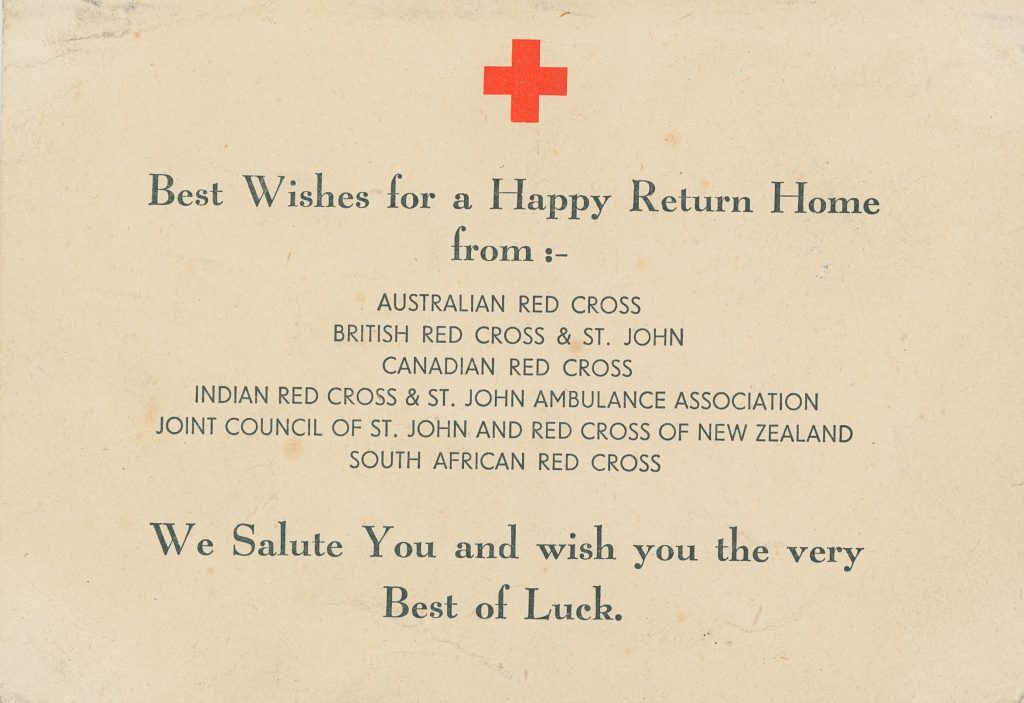

Life in the camps could be harsh: pneumonia and dysentery were rife; prisoners were often used as forced labour; and food was scarce with the men depending on Red Cross parcels.

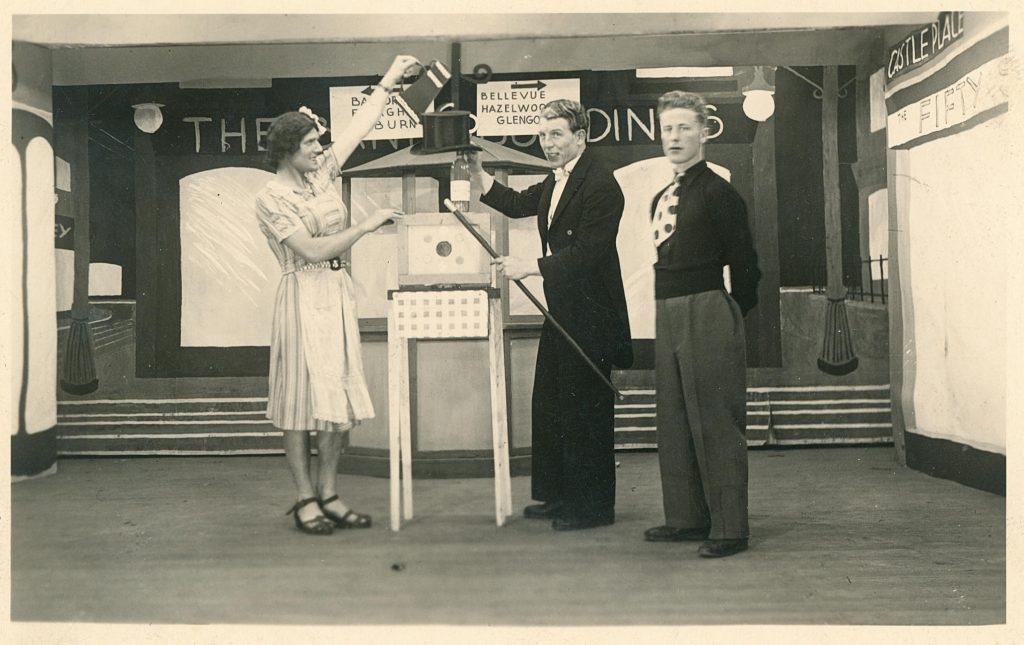

Bert spent five years as a prisoner of war. Arranging entertainments, such as plays, was one way of surviving.

Such camaraderie wasn’t always encouraged in the armed forces. Ernie Richards, who like Cecil was stationed in Iraq, recalled, ‘We weren’t allowed to fraternise with the Indians.’

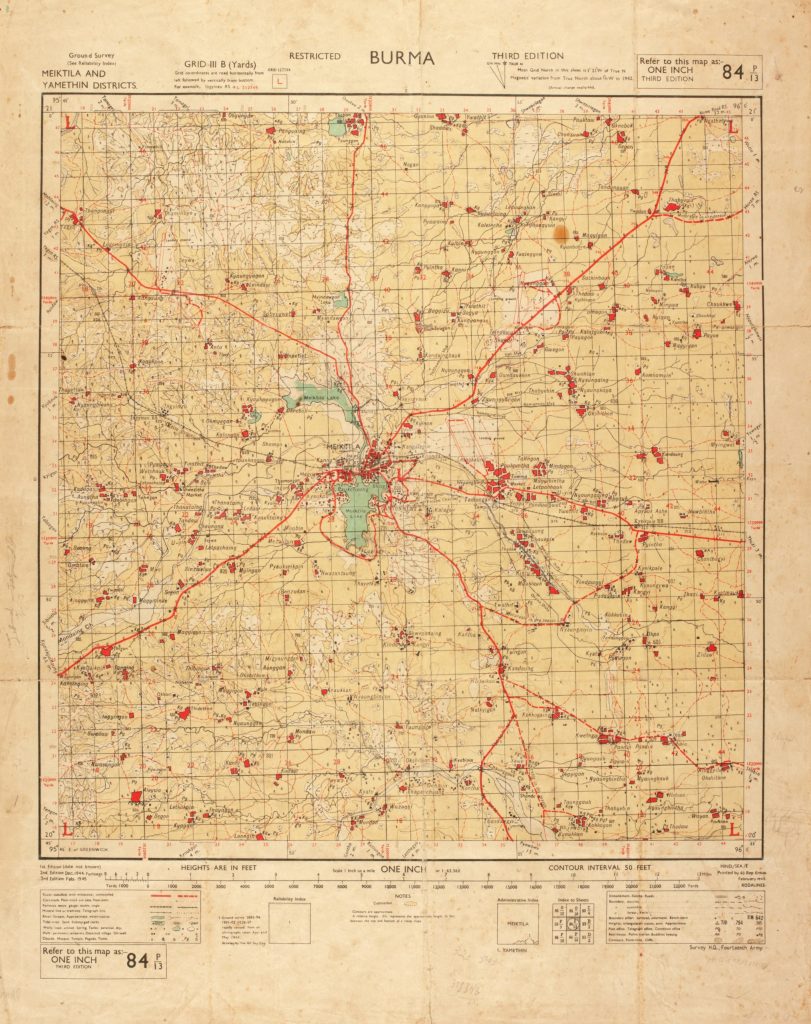

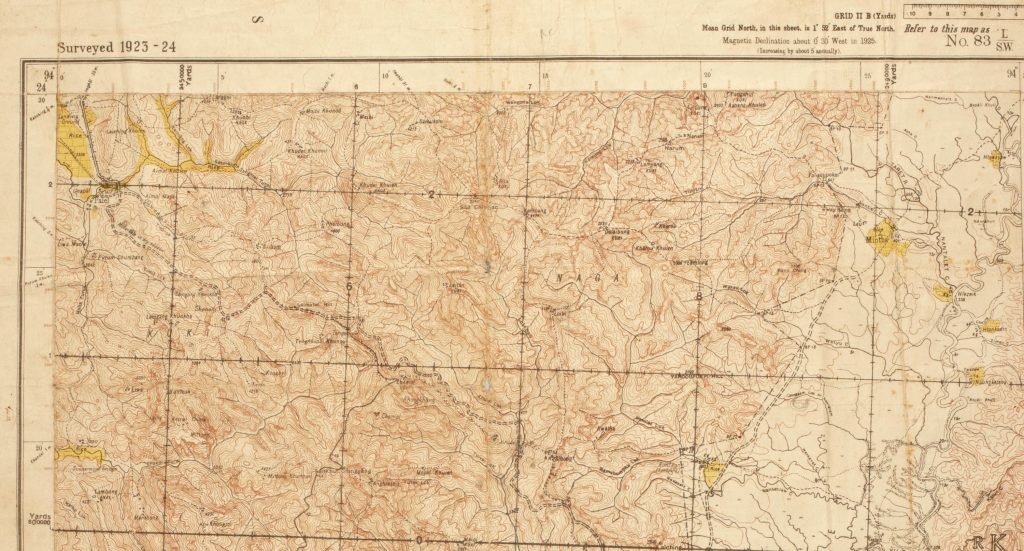

In 1943 Cecil’s battalion sailed back to India and was sent east to the border with Burma, where the Japanese were poised to invade.

‘We spent one week in the train crossing Seilkot to Calcutta and then up the Brahmaputra in a paddle steamer, then changed to a narrow-gauge railway which served the tea estates in Assam, and finally by road to Kohima and Imphal.’

The Japanese wanted to capture Kohima and Imphal so that they could extend their empire into India. They had to do so before their supplies ran out and the monsoon season in June cut off their retreat.

Cecil’s map of the Burma-India border showing the area near where he was stationed

In March 1944 the Japanese attack finally came.

With British and Indian soldiers trapped on Garrison Hill, literally separated from the Japanese by a tennis court, the men were forced into hand-to-hand combat.

The onslaught was relentless, and the brutal and bloody battle – one of the worst of the war – became known as ‘the Stalingrad of the East’.

The isolated position meant that the Allies depended on planes flying in supplies of food and ammunition. Cecil and his men played a key role in the defence of the air strip at Imphal.

‘The Japanese made a night attack in March which failed and we were withdrawn to…hold the vital air strips. This we did until the monsoon broke in June…while the Japanese were cut off from their supplies without reinforcement and starved.’

The map of the world changed dramatically after the war. India finally gained independence, but not without further devastating loss of life, property and livelihoods.

Find out more about the experiences of people during the war at the Northern Ireland War Memorial

https://www.niwarmemorial.org/

21 Talbot Street

Belfast

BT1 2LD

Digital content produced for this project is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Please note: Third-party materials referenced on this website are not subject to this license and retain their original copyright and licensing terms.